Display to header level

Stewardship plans guide management of natural areas by assessing existing conditions, identifying priorities for management, and laying out stewardship tasks. These plans can guide annual work plans and allocation of resources, as well as support applications for funding.

Natural lands offer a wide variety of both stewardship challenges and opportunities for benefiting wildlife and human users. Successfully addressing the challenges and maximizing environmental and recreational benefits requires an on-going commitment to stewardship based upon a long-term view of protecting and enhancing existing natural resources. Developing a stewardship plan is a good process for inventorying existing resources and issues, defining the landowner’s stewardship goals, and designing and implementing strategies for meeting those goals.

The ultimate purpose of any stewardship plan is to provide direction for the landowner or manager to take a parcel of land from current conditions to desired conditions based on the landowner’s goals for the parcel. This might entail a significant change and detailed instructions or a simple plan that confirms or slightly modifies the stewardship activities already in place.

Consider the example of an existing healthy meadow. If your strategy is to create a forest in this area to meet the goal of increasing interior forest habitat, the plan would need to address many challenges involved in conversion of the meadow to forest, including the types and number of trees to plant, when to plant them, and how to protect them from deer and invasive plants over several decades. If your goal is maintenance of the meadow for grassland bird habitat, the plan will codify the current stewardship regimen and address minor issues (e.g., spot-spraying scattered invasive plants) to protect resource quality.

A secondary but vital purpose is continuity; as land ownership or management personnel change over time, a detailed stewardship plan, especially if regularly kept up to date, organizes and transmits the goals, strategies, hard-won knowledge, and other crucial information onward down the line.

The complexity of the plan will depend on the complexity of the parcel’s landscape (the number of different types of land cover like forest, meadow, or developed areas) and the variety of goals the landowner wishes to meet. A stewardship plan also grows in complexity with the degree of degradation of existing resources and how much the area will need to be modified to help meet stewardship goals.

The process for developing a stewardship plan involves ten steps:

Step 1: Inventory existing natural resources and current stewardship issues.

Step 2: Delineate natural lands from the remainder of the property.

Step 3: Establish stewardship units, delineating areas with similar vegetation and past management.

Step 4: Establish the conservation priorities for the natural lands.

Step 5: Establish the stewardship goals for the natural lands in terms of measurable desired conditions.

Step 6: Determine appropriate uses and activities for the natural areas and adjacent buffer lands, considering their compatibility with conservation priorities.

Step 7: Determine appropriate stewardship strategies for each unit.

Step 8: Prioritize and schedule stewardship tasks for each unit.

Step 9: Establish a monitoring program to determine if goals are being met within each stewardship unit over the long term and to increase knowledge essential for improving stewardship over time.

Step 10: Assemble the stewardship plan to record information gathered and decisions made, incorporating a regular schedule of rethinking and revising the plan in response to the results of monitoring and perpetually changing conditions.

Remember that because natural systems are continually evolving, land stewardship must similarly evolve over time as new stewardship issues are identified, land management knowledge and technology change, and stewardship goals are modified. Stewardship plans should be revisited on a regular basis based on monitoring results to make sure they are still appropriate in all respects. A typical monitoring frequency is every 3–5 years, or following a significant change, such as new ownership, modification of the conservation priorities or stewardship goals, or a major unforeseen trend in conditions (e.g., the emerald ash borer crisis of the 2020s). Steps 7 and 8 should be reviewed and revised as needed on an annual basis.

Embedded in the process above is the framework for adaptive ecosystem management (also known as adaptive management), a decision-support concept that is a science-based way of “learning by doing.” Adaptive management is used to manage natural areas despite uncertainties, with a focus on reducing uncertainty over time to improve management. This is done by implementing carefully considered stewardship actions, monitoring the results of these actions, analyzing the trends revealed by monitoring the changes from baseline conditions, and rethinking methods based on the new knowledge. At its highest level, adaptive management involves designing trials of alternative management methods using the principles of experimental design.

Under an adaptive management approach, stewardship actions meet one or more management objectives, and at the same time accrue information needed to improve future management. Adaptive management seeks the optimal balance between achieving the best short-term outcomes based on current knowledge and gaining new knowledge to improve management in the long term.

In brief, the adaptive management framework consists of the following series of tasks, which is continued indefinitely in an iterative (periodically repeated) loop after the first two tasks (see flow chart):

Depending on the resources available and priority of the natural areas being managed, this approach can be taken at different levels, from simple qualitative assessments of the results of stewardship actions to carefully designed trials of management alternatives. This range still ties into the basic concept of assessing stewardship actions to determine their results, adjusting future actions accordingly, and buildin stewardship knowledge.

The first step in developing a stewardship plan is to conduct a baseline assessment of the property to identify the existing natural resources and document any issues that might affect the stewardship or use of the property, a process also called site analysis. A site analysis will:

This process should result in a thorough understanding of the property’s environmental and ecological resources, the threats to the integrity of those resources, and the property’s potential—and limitations—for use.

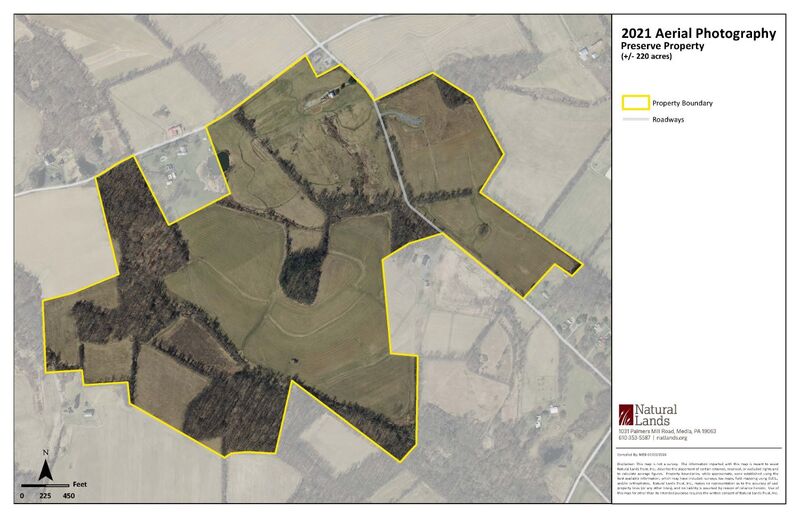

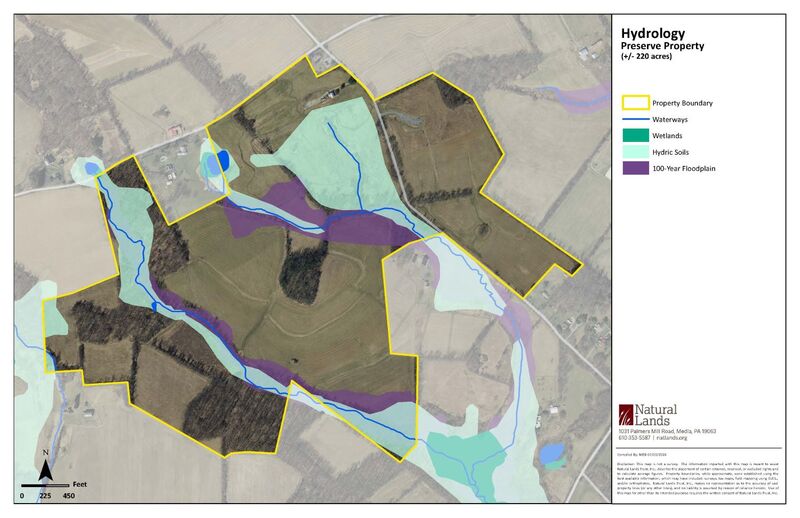

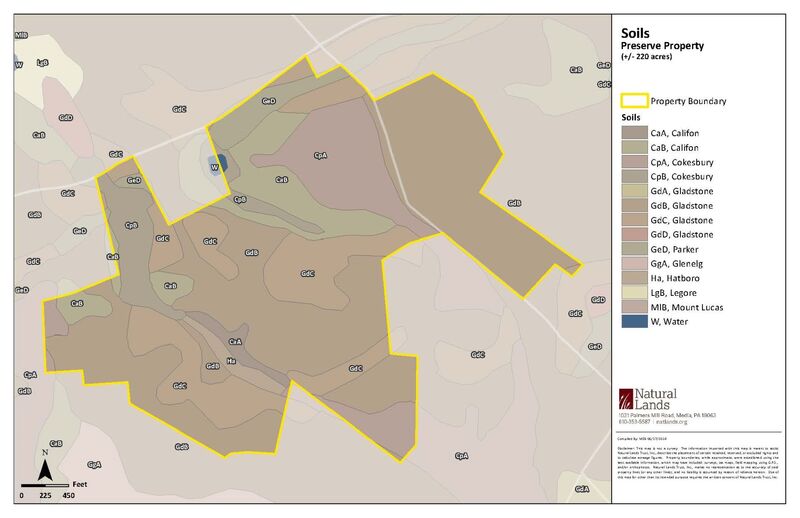

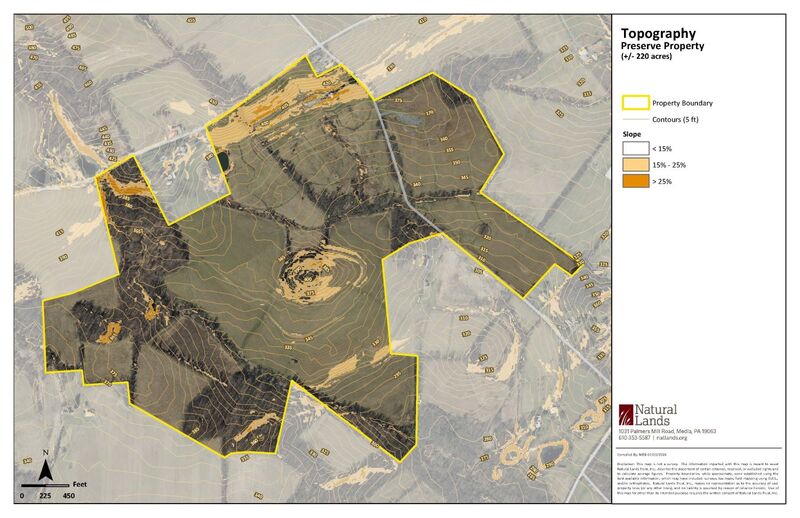

A site analysis starts with a base map, often using aerial photography, showing property boundaries, easements and rights-of-way, adjoining ownership, existing roads and structures, water features, forested and open areas, and any other relevant features. Mapping of the detailed natural features (geology, soils, topography and slopes, hydrology, and vegetation cover), along with existing man-made features such as historic structures, gardens, and landscape elements, is then overlaid on the base map individually or in combination.

Geology and soils will indicate what general type of plant communities—terrestrial (upland) or palustrine (wetland)—would typically occur on various parts of the site. Unusual bedrock types can indicate the potential for uncommon plant communities (e.g., serpentine barrens, diabase glades, calcareous fens). Hydrologic features include surface water features (ponds, streams, springs), wetlands, floodplains, and hydric soils. Moderate (15-25%) and steep slopes (>25%) can also be included. Much of this can be found through online sources, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s WebSoil Survey and Google or Bing maps, and through geographic information systems (GIS) data.

The vegetation information gathered for a site analysis can range from simply listing major cover types (deciduous forest, agricultural field, etc.), to identifying the plant communities present and noting dominant native and invasive species, to undertaking a detailed inventory of species composition and condition of the canopy, subcanopy, shrub layer, and herbaceous layer. Because stewardship largely involves manipulation of plant resources, the greater the detail the better. The level of detail, however, will depend on the available resources of the landowner.

Special features important to note include large trees, plant and animal species of conservation concern (endangered, threatened, near threatened, or rare), patches of uncommon wildflowers (especially spring ephemerals), vernal pools, and other wetlands. Stewardship issues that might be encountered include lack of native plant advance regeneration, invasive species, erosion (due to on- or off-site uses or problems), lack of an adequate riparian buffer, old structures, hazard trees, and dumps. While much of this information can be gathered from field visits, online sources can also be great sources of information. For instance, information on whether rare, threatened, or endangered may be present can be found through the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program’s Conservation Explorer.

An effective site analysis should seek to assess the key features and identify possible issues. While inventories are important for site analyses, they can be resource intensive. Different levels of inventorying and site analysis can be thought of as Good, Better, and Best, depending on how detailed they are. While the Best category can be considered the “gold standard,” any of the three levels can provide valuable insights into the site conditions.

The level of detail for an inventory may vary by the property and by the resources being inventoried. Some properties that have very simple vegetation covers or that have few monetary/labor resources available to carry out an inventory may have a relatively simple site analysis, taking a “Good” approach. If a landowner knows already knows there is a unique resource present, such as a rare plant community, a more detailed inventory at the “Better” or “Best” level may be more appropriate if resources are available. The indicators and the methods used to measure such resources during the site analysis could serve as the baseline assessment for a long-term monitoring program (more on this under Step 9). The level of detail for the site analysis can vary across a property depending on the importance of the various natural resources present and the monetary/labor resources available to carry out the inventory.

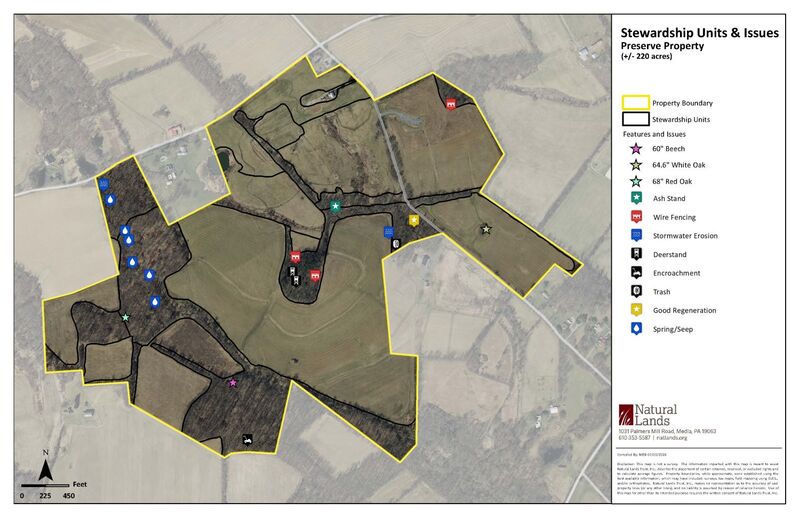

Below are examples of detailed maps showing a range of spatial characteristics that can be cataloged for a site analysis. A simplified site analysis map, which could be appropriate for some properties, is included in the next section below.

The next step in developing a stewardship plan is to use the information gathered through the site analysis to determine which areas of the property will be designated as natural lands and addressed under the plan. For the purpose of this stewardship handbook natural lands are considered those areas with plant cover that does not receive or require ongoing, intensive management—as do agricultural or landscaped areas—to perpetuate.

For many properties, the general limits of the natural lands are easy to establish. They are basically the areas outside of the landscaped, developed, and agricultural (cultivated fields, pastures, orchards) areas on the property. What will require some thought is: (1) whether any part of the current natural area will be used for other purposes in the future, such as the site for a house or playing field; or (2) if any of the current area in landscape plantings, lawn, or agriculture can be converted to natural lands.

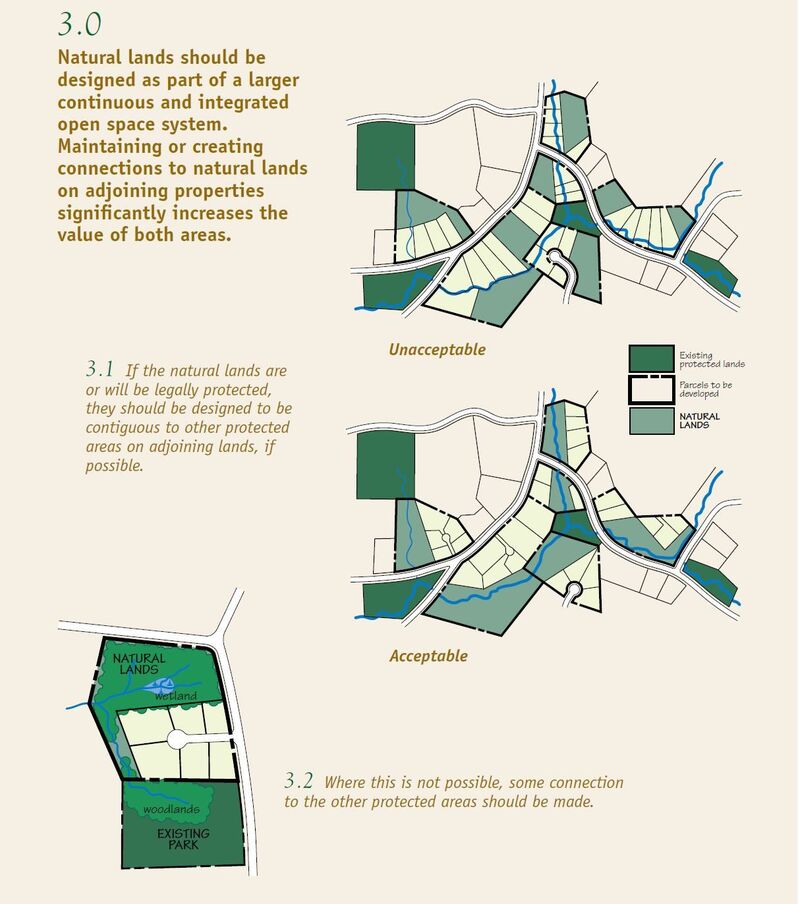

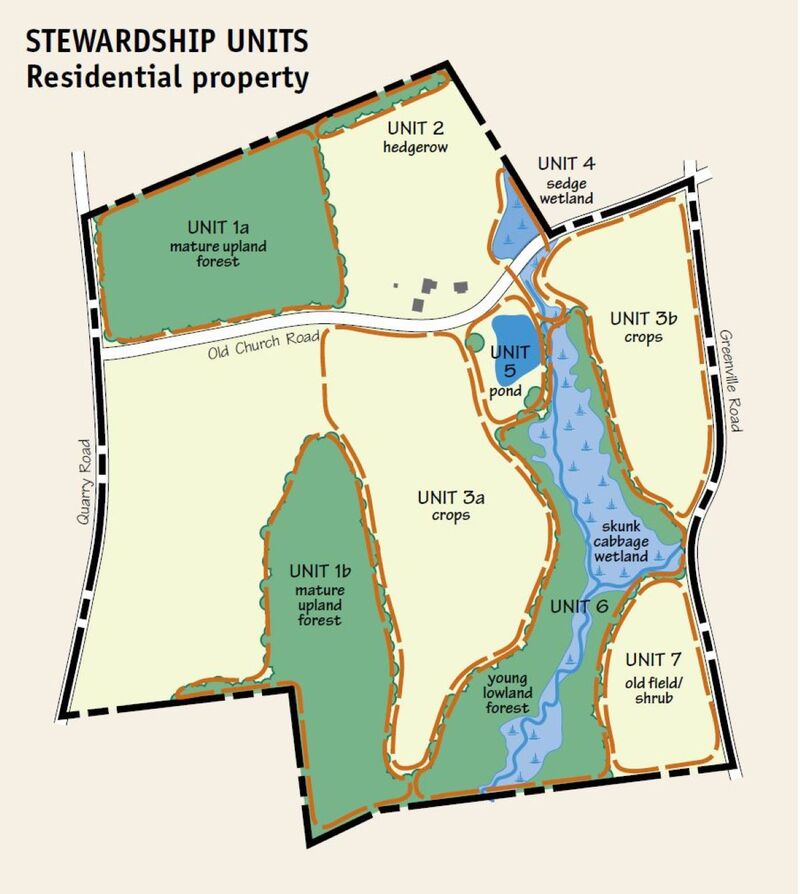

To illustrate this step, we will consider two scenarios: (1) delineating natural lands on a residential property; and (2) delineating natural lands for a conservation subdivision (a residential development designed to protect existing natural lands within the subdivision area rather than clear-cutting large areas for buildings). Using the site analysis map below for the first scenario, we can delineate the natural lands most easily by outlining and excluding the areas that will be maintained in formal landscaping (areas that will be maintained as lawn, gardens, or intensive recreation sites) or managed for agricultural purposes (crops or pasture for livestock). As the property is used now, the natural lands would include the forest, hedgerows, wetlands, and old field/shrub areas.

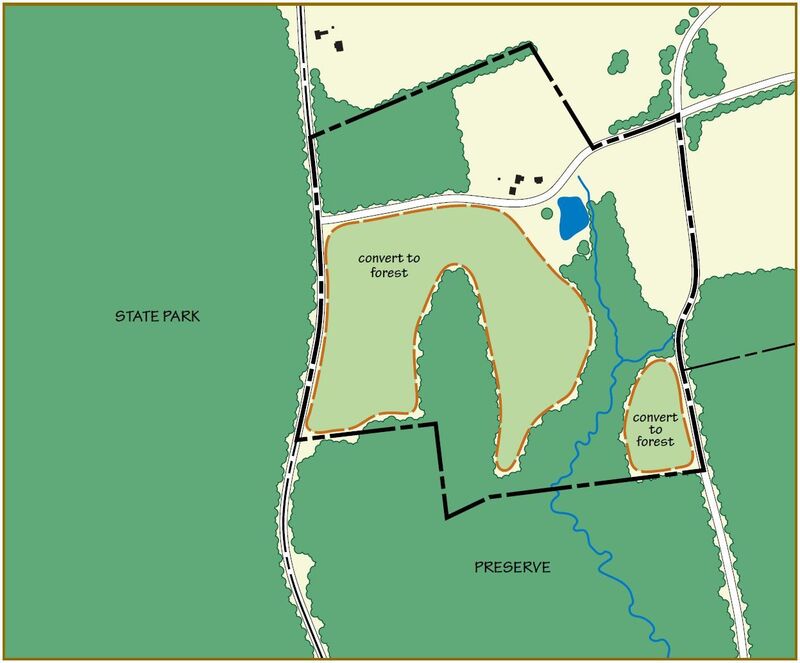

Additional parts of the property could be added to the natural areas depending on the specific conservation priorities and the financial resources of the landowner. For example, if a conservation priority for the property is to protect the stream and the landowner no longer needs the income generated from the crop fields, the crop fields could be converted to forest or native meadow to better buffer the stream. The area around the pond could also be converted to native meadow or forest to shade the water surface, discourage resident Canada geese, and improve habitat for less common waterfowl and other wildlife. This example is illustrated in the second map below.

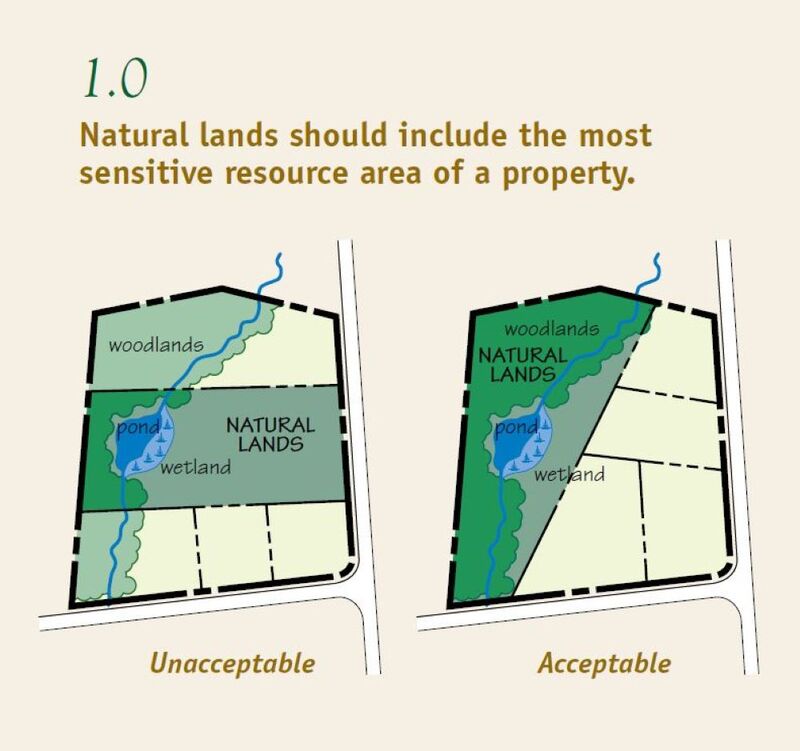

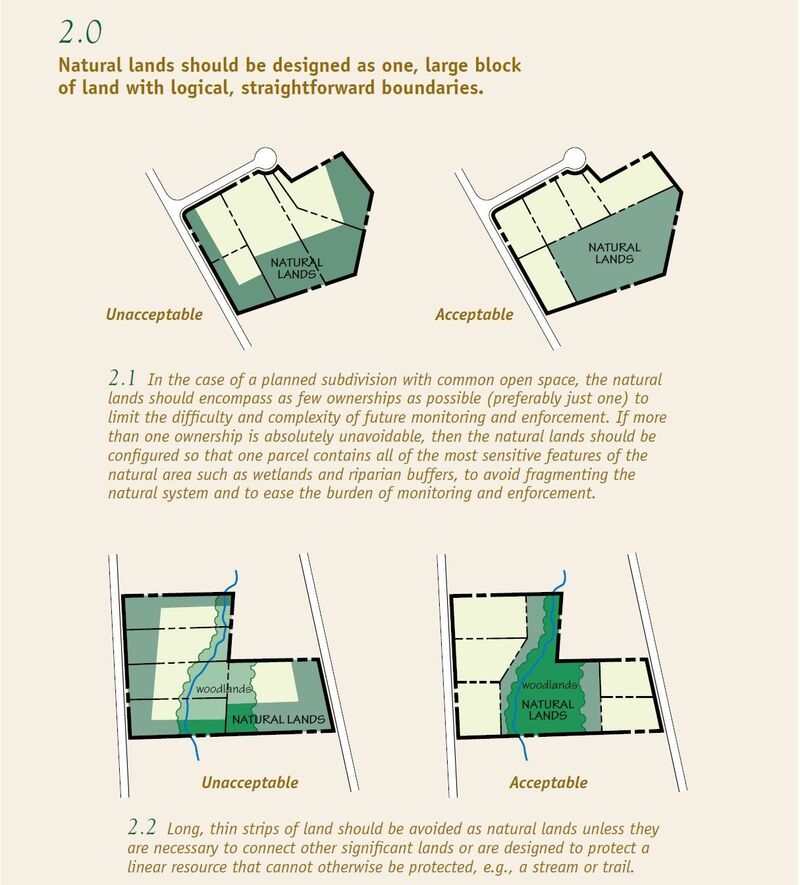

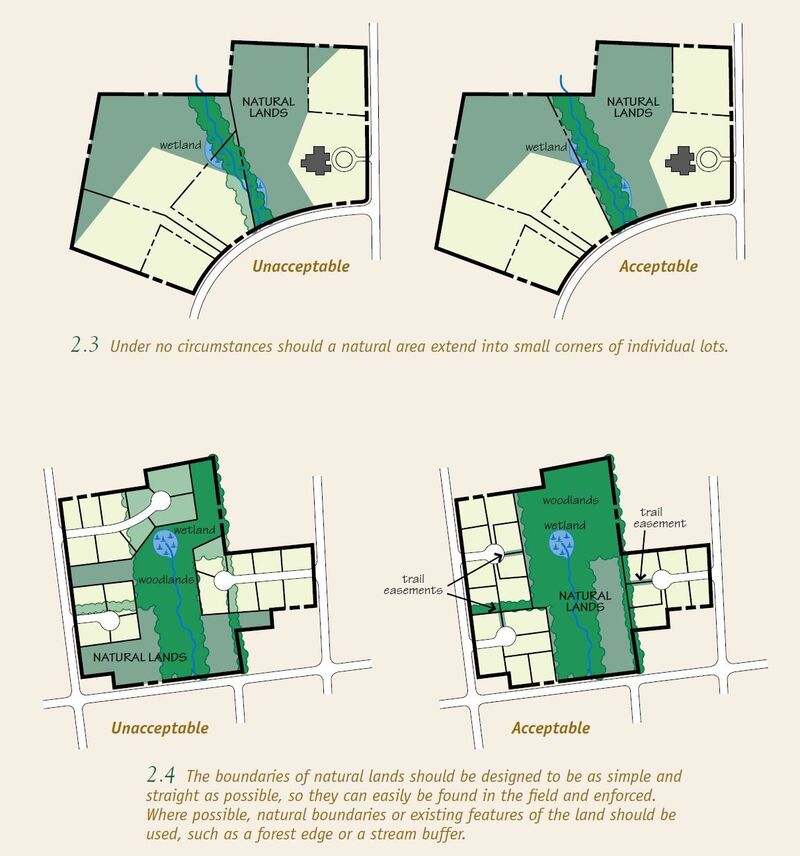

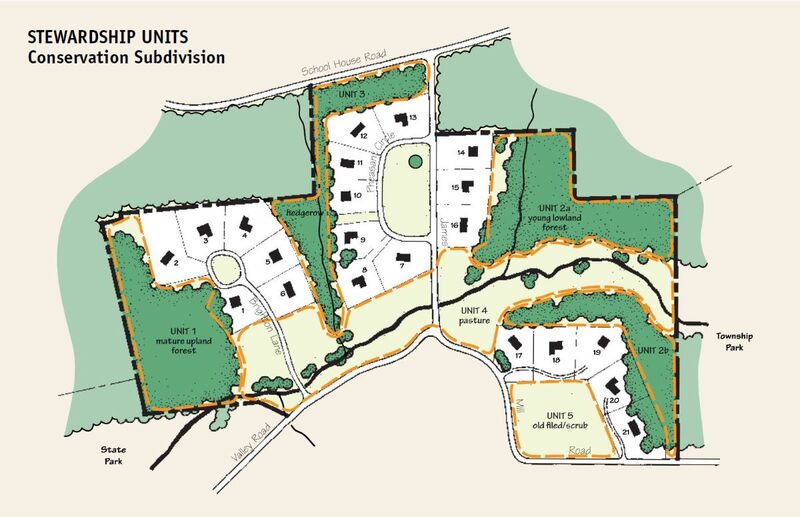

The second scenario, delineating natural lands for a conservation subdivision, is more complicated because you also need to delineate multiple residential lots. The following examples illustrate simple design guidelines for refining the boundaries of the natural lands. Following these guidelines will result in the design of better, more effective natural lands that meet the conservation goals of the municipality and landowner, maximize environmental and ecological benefits, and are easier to steward.

Unless the property is very small, its natural lands will usually consist of more than one cover type. Because stewardship goals, strategies, and tasks are often different for different cover types, it is helpful to separate areas with different cover types—or disconnected areas with the same cover type—into stewardship units. Delineating stewardship units on a map creates a common view and vocabulary for the property and allows you to discuss the current features and condition of each area of the property more clearly with stakeholders (family, residents, constituents, staff), consultants, and contractors.

The first map below shows the stewardship units for the residential property scenario from Step 2.

This second map is an example of a fully designed conservation subdivision with stewardship units.

Natural lands are conserved because they have some type of importance, or conservation value, to current or former decision-makers. Examples of conservation values include:

The decision-maker or -makers are those who placed a legal restriction, such as a conservation easement or deed restriction, on the property title or the person or entity (corporation, municipality) who currently holds legal title to the land. They may be supported by boards, other staff including managers or partners, or others with knowledge of or interest in the property and natural resources.

The site analysis will, in most instances, identify more than one conservation value. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to steward natural lands in a manner that protects and enhances every conservation value of a site due to resource constraints. The critical decision that must be made in developing a stewardship plan is which conservation values are most important, in other words, what are the conservation priorities. The conservation priorities are the engine that drives future stewardship decisions for the natural lands. Stewardship decisions should primarily focus on protecting and enhancing the highest conservation priority or priorities of natural lands. It is likely that there will be multiple conservation priorities, particularly for very large properties, but more than two or three will muddle the decision-making process. As resources allow, other conservation values can be addressed over time, but resources should first be directed to maintaining or improving the conservation priorities.

What or who determines the conservation priorities of each site? While the relative importance of all conservation values should—and usually does—figure prominently in this decision, the highest conservation priority or priorities are ultimately determined by those with legal authority over the property. The following decision tree will help you determine the conservation priorities for the natural lands of any site.

1. Do any legal documents, for instance, the will of the former owner, a conservation easement, a deed restriction, municipal open space plan, or subdivision approval, specifically dictate how the natural lands should be used or managed? Examples could include: the site must remain in a particular condition (forest, meadow, agriculture); be managed for a specific species or group of animals (bog turtle, forest-interior birds); or used for environmental education.

2. Are there any features protected by federal regulations? Plant and animal species listed on the federal endangered species list (e.g., bog turtle, rusty-patched bumble bee, Indiana bat, eastern massasauga) are protected from activities that threaten the viability of a local population. Landowners with a listed species on their property should consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service before undertaking any activity within the property; you will be given an Incidental take permit if the activity will not harm the species. Although you do not violate any law by not consulting with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, if you proceed with an activity that does harm the population, you can be prosecuted under the Endangered Species Act. The Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program’s Conservation Explorer online mapping tool can be used to help determine if any protected species may be present.

3. Does the current landowner have a specific conservation interest? Without any specific legal restriction or federally regulated resource on the property, the current landowner has the authority to determine the stewardship of any property within the guidelines of local ordinances. The landowner may have a specific interest for the natural lands such as environmental education or habitat enhancement for grassland birds.

4. Can the property help protect or enhance a local, regional, or statewide conservation priority? In many cases, the former or current decision-maker did not or does not have a specific stewardship interest, but instead desires to see the property used to support a general interest such as wildlife habitat, the protection of a high-quality stream, or as a place for private or public recreation. While these interests will need to be addressed in the stewardship plan, their more general nature allows the conservation priority to be shaped by other conservation considerations and to change over time as the needs and concerns of the landowner or general conservation community change.

To determine how best to use the property to fulfill general conservation goals, it is helpful to understand the conservation priorities of local, regional, or statewide organizations and agencies and to view the property as part of a larger landscape. Helping to address a larger conservation priority could help determine the conservation priorities of the property. This can be done by researching regional and state-level plans such as strategic plans for the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources’ Conservation Landscapes the Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan (see Related Library Items).

Looking more locally, using the residential scenario from Step 2, the two maps below provide a simplified illustration of how the surrounding landscape might influence your choice of conservation priority. The first map shows the property within a large, forested landscape. Converting the open areas to forest would significantly add to interior forest habitat to the benefit of songbird species of greatest conservation need. On the other hand, if the property rested within an open landscape of farmland and meadow and the more isolated forested areas on the property are heavily degraded, it might be best to convert them to native meadow to expand interior habitat for grassland bird species of greatest conservation need. These two examples show that the same general landowner interests (wildlife habitat) can result in very different conservation priorities depending on the landscape context.

Once you have determined the conservation priority or priorities for the natural lands, you are well on your way to establishing the stewardship goals, that is, the desired future condition and use of the natural lands. The first stewardship goal should always be to protect and enhance the conservation priorities of the property. There can be many other stewardship goals, but none should conflict with this overarching goal. From the examples of conservation values in Step 4 above, the stewardship goals could be as follows:

Primary goal

Secondary goals

To make stewardship goals more feasible and concrete, land managers should identify the desired conditions for an area based on these goals. The desired conditions are the selected outcome for an area based on a set of ecological indicators, such as type and abundance of vegetation, water quality levels, habitat conditions, or number of breeding pairs of bird species of greatest conservation need. These ecological indicators are determined by the land manager or whoever is compiling the plan. Ecological indicators should be monitored over time to determine if progress is being made towards desired conditions. These indicators can be qualitative or quantitative, depending on the indicators chosen and available resources for monitoring.

For example, if the stewardship goal is to protect and enhance the forest bird species of greatest conservation need, the desired condition may be a mature forest with at least 100 acres of interior forest dominated by oak and hickory species with a dense understory of native plants. Ecological indicators could include:

Understanding the difference between the current condition and the desired condition will help land managers see how much work may be needed. This will help them chose a sustainable course of action based on available resources (see Sustainable Stewardship).

The existing resources, conservation priorities, and stewardship goals will determine what may be appropriate uses for the site. This depends largely on the sensitivity of the site and the level of disturbance associated with potential activities. For areas with endangered, threatened, or rare species throughout the entire site, the only appropriate uses may be conservation of the natural resources and scientific studies. For areas where the main conservation priority is focused on recreation or where the natural areas are less sensitive, more recreational uses ranging from earthen trails to more intensive recreation like disc golf, equestrian use, or paved trails may be appropriate.

Uses should be evaluated over time to monitor if they are having significant impacts on the surrounding natural areas. If damage does occur, the use or its implementation should be reconsidered to better protect the natural resources.

Once goals are set for the entire area of natural lands within a property, stewardship strategies to achieve them can be established for each stewardship unit. Simply stated, the strategies lay out what will happen over the coming years in each unit to further the stewardship goals of the entire area of natural lands. Stewardship strategies should generally increase the environmental and ecological values of a unit while meeting a stewardship goal. The following are examples of common stewardship strategies.

Vegetation Management

Wildlife Management

Improving Aesthetics and Eliminating Hazards

Stormwater Management

Public Use

The next step in creating a stewardship plan is determining what tasks need to be done and in what order to implement the stewardship strategies and achieve stewardship goals.

Stewardship tasks are generally divided into restoration tasks and routine tasks. Restoration tasks typically require a concentrated effort for a relatively short period of time. The need for them is often a legacy of insufficient resources, interest, or knowledge to perform routine tasks (such as invasive species control, deer management) in the past or the result of an unexpected disturbance, for example, tree blowdowns from high winds, erosion from heavy rain, or illegal dumping. Routine tasks are ongoing (monitoring for unwarranted use or hazards, mowing trails, equipment maintenance) or cyclical (cutting vines in the winter, mowing or burning meadows in early spring, administering a controlled deer hunt).

Restoration and routine tasks are largely outgrowths of the stewardship strategies for the natural lands. Unless time or financial resources are unlimited, you will need to prioritize tasks to have the greatest impact with the available time and money.

The following are general guidelines for ranking the priority of restoration tasks, starting with the most urgent.

This should not be viewed as a list to be completed sequentially, but it is the typical order of importance or urgency of restoration tasks. In many cases these tasks will require the services of contractors or volunteers, which can complicate the logistics of starting the work. Also, because financial support is sometimes available through grants from public agencies, watershed associations, business-sponsored environmental, etc. for restoration tasks (tree planting, erosion control), implementation can be delayed by administrative requirements (e.g., grant applications, budget approvals) or sped up by the provision of funding.

The timing of routine tasks is generally dictated by the season (see table below). Routine monitoring of property boundaries, hazard trees, and invasive species is often best done during the winter months when access to and visibility within natural lands is best. Meadow mowing has the least impact on wildlife in late winter (prior to March 15); trail mowing needs to occur throughout the growing season. Time available for deer management using recreational hunters is restricted to the seasons set by the Pennsylvania Game Commission.

Stewardship Task Schedule (linked table)

An example schedule of stewardship tasks

To most efficiently and effectively meet the conservation goals established in a stewardship plan, environmental and ecological changes—those resulting both from management activities and from new influences on the property—should be tracked, in terms of the same indicators of ecological quality and condition inventoried in the original site assessment. With periodic feedback as to which stewardship activities are or are not working, together with increased knowledge and new technologies, the stewardship of natural areas can be modified to better achieve established conservation goals. There should also be periodic (at least annual) monitoring to identify new disturbances (dumping, new invasive species, erosion) so they can be addressed as soon as possible.

Monitoring involves collection and analysis at regular intervals of data (quantitative measurements or qualitative observations) on indicators selected to evaluate change or progress toward meeting stewardship goals, that is, attaining desired conditions. Monitoring and analyzing trends over time generates practical new knowledge that can be promptly put to use. It is in essence a performance evaluation—a systematic, disciplined approach to measure and improve the effectiveness of management. Monitoring is vital to build in consistency, rigor, and efficiency in measuring progress toward achieving and sustaining desired conditions.

Not all land stewards have the staff and volunteer capacity, available expertise, or funding to monitor as thoroughly as might be considered ideal. The level of monitoring will depend on the resources available and the level of priority. If endangered species or ecological communities of high conservation significance are involved, the most stringent level of monitoring is appropriate and necessary. In more ordinary situations, a simpler and less demanding set of monitoring methods may be all that is needed. Land managers will have to assess what resources are available and prioritize what level of monitoring is feasible and necessary. The level of monitoring is likely to vary across what is being monitored; the same in-depth monitoring may not be needed to track all stewardship activities or to monitor all resources.

Volunteers, particularly students and professors or teachers from nearby universities, colleges, and high schools and skilled recreational birders, butterfly-watchers, and others can help with monitoring, whether it is modest in scale or done by a professional ecologist to the most stringent standards. This can help reduce the costs of expertise and labor to meet monitoring needs.

The final step in preparing a stewardship plan is organizing all the information gathered and decisions made in a single document, online folder, or database entry. The resulting stewardship plan becomes a handy reference and a reminder of stewardship strategies by management unit that will guide the development of a task list each year.

The stewardship plan is intended to be a living document—growing as new information is learned about the property and evolving as monitored trends are analyzed, conditions change, and conservation priorities change. As such it should be regularly revised, such as on a 5-year cycle or after significant changes to the site’s natural resources or property boundaries. The following is a sample outline for constructing a stewardship plan.

Stewardship Plan Table of Contents (linked TOC)

Stewardship Plan Summary (linked table)

Department of Conservation and Natural Resources’ Conservation Landscapes (https://www.dcnr.pa.gov/Communities/ConservationLandscapes/Pages/default.aspx, as of 2024)

Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program: Conservation Explorer [https://conservationexplorer.dcnr.pa.gov/, as of 2024]

U.S. Department of Agriculture: Web Soil Survey [https://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/, as of 2024]