Display to header level

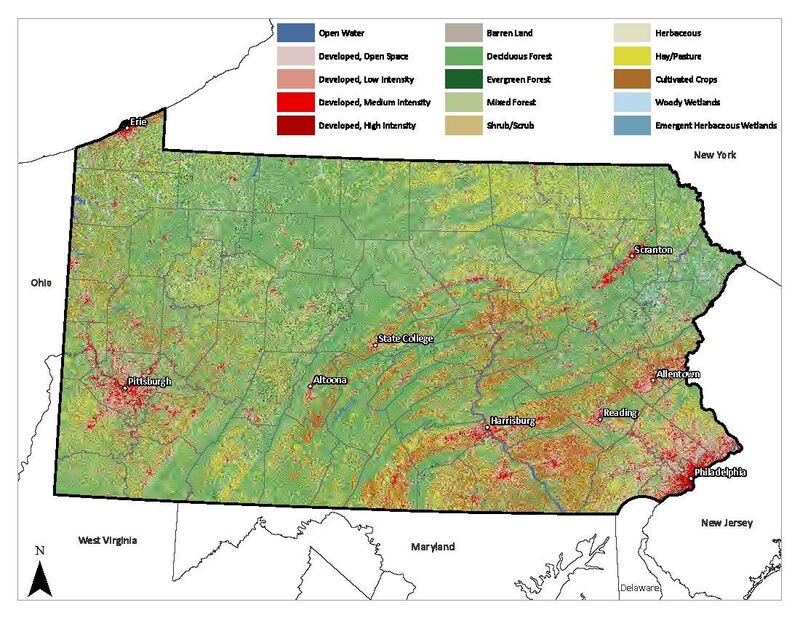

It is important for a land steward to understand the natural resources of an area. What resources are present have implications for management, mainly for how to care for the land and its ecosystems but also for what types of recreation, if any, may be appropriate. This chapter summarize the major natural resources of Pennsylvania.

It is important for a land steward to understand the natural resources of an area. What resources are present have implications for management, mainly for how to care for the land and its ecosystems but also for what types of recreation, if any, may be appropriate. The following sections summarize the major natural resources of Pennsylvania. The Preparing a Stewardship Plan chapter explains how to assess natural resources at a more local scale.

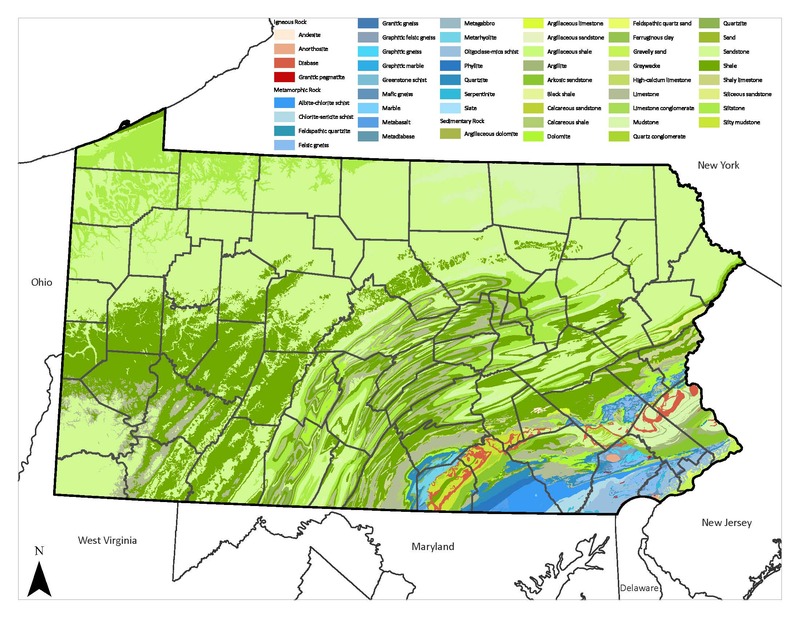

The types of rock formations that form the foundation of Pennsylvania are quite diverse. All three types of rock—igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary—are found in Pennsylvania. A long history of folding and compression during continental collision and mountain-building events and intrusion of volcanic material has left a legacy of rock types at the surface ranging from soft limestones and shales to very durable sandstones, gneiss, diabase, and quartzite. Igneous and metamorphic formations (crystalline rocks) and some sedimentary rocks are found southeast of Kittatinny Mountain, the southeasternmost ridge of the Appalachian Ridge and Valley region. Sedimentary rocks and deposits of glacial rubble from the past several Ice Ages are found in the rest of the state.

Sedimentary rocks, shown in shades of green, are the predominant bedrock type across most of Pennsylvania. Igneous and metamorphic rocks are concentrated in the southeastern part of the state.

Sedimentary rocks, shown in shades of green, are the predominant bedrock type across most of Pennsylvania. Igneous and metamorphic rocks are concentrated in the southeastern part of the state. Typically, hard rocks form the high lands and soft rocks the lower-lying areas, as the softer rocks erode more readily. Different rock formations vary in porosity; each formation allows groundwater to pass through rapidly or slowly (or not at all) to feed streams and rivers through springs and seeps. Generally, softer rocks are more porous and allow greater groundwater flow. Rivers and streams redistribute and sort gravels, sands, and boulders eroded from the rock formations they flow over and past.

Over the past two million years, continental glaciers covered large portions of northeastern and northwestern Pennsylvania several times in ice nearly a mile thick. Like giant conveyor belts, the glaciers moved great amounts of material from the north (glacial drift), leaving distinct topographic features upon their retreat. Glacial landforms include moraines, outwash plains, kames, eskers, and kettle holes. These landforms are also significant drivers of plant community composition.

Bedrock or unconsolidated material such as glacial drift are the parent material from which soils develop through processes of chemical weathering, leaching, and mineral redistribution, creating distinct layers—soil horizons—which are visible when digging. In wetlands, particularly bogs and fens (also called peatlands), the parent material is partially decomposed organic materials, or peat. Differences in chemical composition of rocks have a strong influence on soil. Taken together, soil moisture and soil chemical composition tend to be the strongest influences on soil fertility.

Much can be predicted about the types of plants that will grow on a site by understanding the type of soil occurring there. Extreme wetness or dryness in soils creates stress for plants and specialized floras typically grow in these locations. In between the harsh conditions imposed by wetness or dryness, plant growth is strongly determined by soil fertility. Descriptions of soils through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s online Web Soil Survey is useful in determining whether a soil is extremely wet or dry and fertile or infertile. Fertility can be related to geology, with quartzite and many sandstones and shales producing lower fertility soils and gneiss, limestone, diabase, schist, and some shales and sandstones producing richer soils. Most native plant communities are highly tolerant of low soil fertility and are often outcompeted on high-fertility soils by invasive species.

Pennsylvania also has some very unusual soil types based on geology. For instance, in the southeastern part of the state, soils derived from serpentinite rock can be toxic to most plants where the soils are thin and where organic material has not accumulated sufficiently to buffer the chemical effects of the bedrock. Only certain plant species tolerate serpentine soils. The plant communities that grow on serpentine soils, called serpentine barrens, harbor many state and globally rare species.

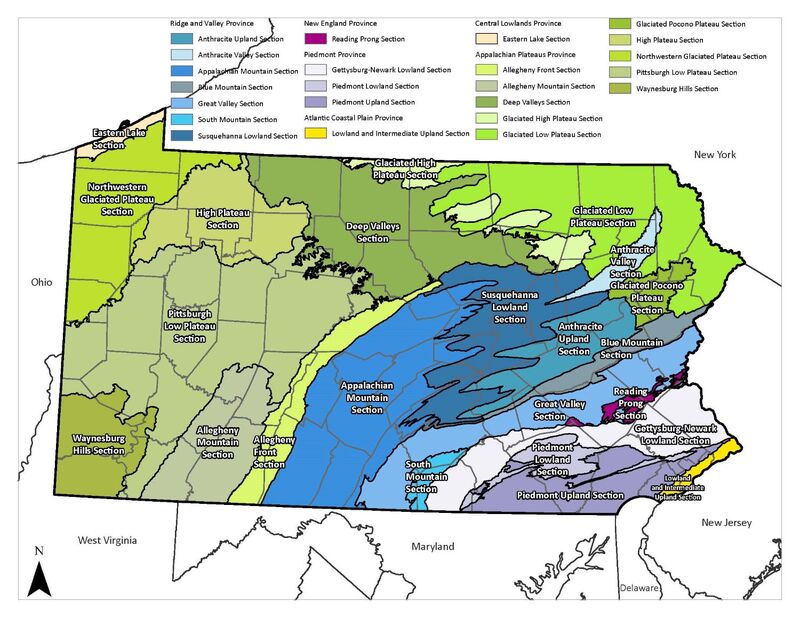

Pennsylvania is divided into six physiographic provinces with three of those provinces divided into numerous sections. These provinces and sections define unique geologies. The regional flora of the state, although not strictly defined by these divisions, is strongly influenced by the underlying and surficial geology, leading to associations between plant species and provinces.

The Atlantic Coastal Plain is a thin strip of land along the Delaware River at the southeastern edge of the state. There is no hard bedrock near the surface; soils are weathered from gravel, sand, silt, and clay deposited mainly during the most recent Ice Ages. The soils range from very wet to very dry, depending on how close the water table is to the surface. Moving north and west from the Delaware River, the Atlantic Coastal Plain transitions to the Piedmont province, which does have hard bedrock near the surface. This transitional area, known as the Fall Line, is most noticeable along streams as the location of steep-sided valleys, rapids, and waterfalls. Because the Fall Line was the limit of navigation on rivers by early European settlers and the fast waters of smaller streams provided power for mills, it is where many towns and cities were founded, including Philadelphia on the Schuylkill River and Trenton, New Jersey, on the Delaware River.

The Piedmont province is divided into three sections by major rock types. Closest to the Atlantic Coastal Plain is the Piedmont Upland, consisting of rolling hills with a foundation of schists and gneisses (relatively hard rocks) with the schists typically weathering to higher-fertility soils than the gneisses. To the north and west is the Piedmont Lowland, a narrow limestone valley within Chester and Montgomery Counties with rich soils that is locally known as the “Great Valley” (not to be confused with the much larger Great Valley section of the Ridge and Valley province to the north from Northampton to Franklin Counties). Much of this area is heavily settled (including the towns of Coatesville, Downingtown, and King of Prussia) with attendant industry, commerce, and roadways. Beyond the Piedmont Lowland is the Gettysburg-Newark Lowland. The bedrock in this section consists of schists and gneisses in places but is dominated by red shales, sandstones, and conglomerates, punctuated by hills underlain by diabase, an igneous volcanic rock.

The Ridge and Valley province (also called the Valley and Ridge province) is characterized by parallel, forested, sandstone and shale ridges divided by long, continuous valleys with fertile limestone soils. The Great Valley section of this province adjoins the Piedmont. The Appalachian Mountain section is the largest section in this province, extending from the Maryland border through Bedford, Fulton, and western Franklin Counties to near the Susquehanna River’s West Branch and main stem south of the West Branch-North Branch confluence. Northeast of that section are the Susquehanna Lowlands— the second-largest of the Ridge and Valley sections. The other sections are Blue Mountain, South Mountain, Anthracite Upland, and Anthracite Valley.

Adjoining the Ridge and Valley’s Great Valley section and the Piedmont’s Gettysburg-Newark Lowland section is the southernmost section of the New England province, called the Reading Prong. It consists of rounded ridges of granitic gneiss and quartzite that are highly resistant to erosion.

The Appalachian Plateaus province is by far the largest province in the state. It is characterized by relatively uplifted but unfolded rock formations. It includes the Allegheny Front, an escarpment that defines the southwestern half of the boundary with the Ridge and Valley province; the Allegheny Mountain section, an older and more erosion-resistant formation than the Appalachians; the Pittsburgh Plateau and Waynesburg Hills sections, which are rich in coal deposits; the unglaciated High Plateau and Deep Valleys sections, underlain by sandstone geology and featuring deep gorges formed by streams eroding through the once-level plateau; and the glaciated northwest (Northwestern Glaciated Plateau) and northeast (Glaciated Low Plateau, Glaciated High Plateau, Glaciated Pocono Plateau) sections which are rich in wetlands and numerous glacial features. The Northwestern Glaciated Plateau section is underlain by limestone-rich glacial drift, which weathers into soils that shape unusual plant communities known as calcareous wetlands.

The Central Lowlands province in Pennsylvania includes only the lake plain of Lake Erie and the numerous streams that extend from the Northwest Glaciated section to Lake Erie. Calcareous parent material brought down into the region by a vast glacier during the most recent Ice Age and landforms left by that glaciers’ retreat contribute to the rich plant communities found in this province, particularly the wetland communities.

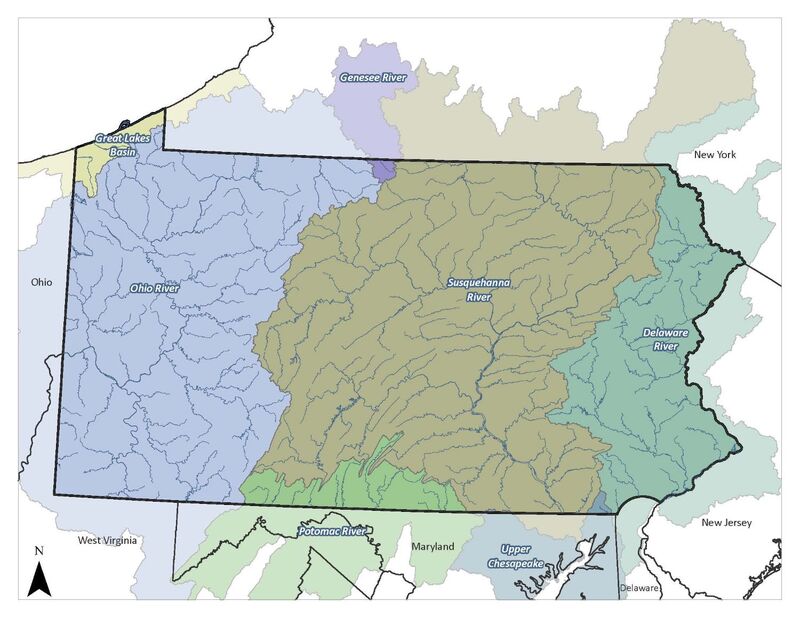

Water resources are generally divided into groundwater and surface water. As the names imply, groundwater is the reservoir of water in fissures and porous rock located below the soil surface and surface waters are visible aboveground, including wetlands, ponds, lakes, and streams. The land area that drains to a network of ground- and surface waters is known as a watershed. All watersheds eventually drain into a major river basin and then into an ocean.

There are six major watersheds that cover Pennsylvania: the Ohio River, Susquehanna River, Delaware River, Potomac River, Genesee River, and the smaller-stream watersheds of the Great Lakes basin. Five of Pennsylvania's major watersheds are part of the Atlantic slope drainage basin, which drains to the Atlantic Ocean. They are the Delaware, Potomac, Genesee, Great Lakes, and Susquehanna watersheds. The Ohio River watershed is the lone watershed that is part of the Mississippi and Gulf of Mexico drainage basin.

There are pronounced differences in the fauna (especially freshwater mussels and fish species) between the Atlantic and Mississippi drainages due to millions of years of separation. Land-use history and current land use greatly influence the aquatic biodiversity in our watersheds at the scale of individual streams.

The three largest watersheds in the state each have tributaries (West Branch Susquehanna River, Clarion River, Lehigh River, and Monongahela River) that have been heavily impacted by coal mining and steel production. There have been substantial improvements in water quality since the 1970s as active mining, especially strip mining, has slowed and active remediation projects have helped to lessen inputs into the rivers. Aquatic communities are rebounding to some extent. With continued improvement and active stewardship (e.g., mussel reintroduction), they will continue to diversify and recover.

Groundwater quantity is partly determined by geologic formations but is everywhere vulnerable to contamination from failing septic systems, livestock, pesticides and herbicides, and leaks and spills of toxic substances. The County Conservation District or Natural Resources Conservation Service can provide groundwater information for specific areas.

Maintaining and enhancing the health of local watersheds requires a focused strategy that includes:

Ecologists have noted for centuries that plant species tend to sort themselves out in a pattern of roughly repeated assemblages (ecological communities) across the landscape. Several classification systems have been devised to catalog this phenomenon. This handbook uses the plant associations presented in the Pennsylvania Plant Community Classification (see Related Library Items) to describe the various plant communities that are found within Pennsylvania.

In general, plant communities are divided into two major groups—terrestrial and palustrine—depending on the hydrologic characteristics of the site where they occur. A third group, aquatic communities, including the underwater and emergent plants of streams, lakes, and ponds, is not covered in this Handbook. In this context, terrestrial corresponds closely with “upland” and palustrine is synonymous with “wetland.” Palustrine communities are typically found along streams and rivers and in areas with a shallow water table. These two categories are each broken down further into forest, woodland, shrubland, and herbaceous openings. Forests, which cover most of the region’s natural lands, are dominated by trees, where the leaf canopy is closed or nearly closed and the majority of tree crowns are overlapping, typically with between 60% and 100% tree cover. Woodlands are also tree-dominated, but are more open in character and have between 25% and 60% tree canopy cover. Shrublands are dominated by shrubs and small trees, with herbaceous plants present in more open areas. Herbaceous openings are communities dominated by plants with no persistent woody stem, such as graminoids, forbs (wildflowers), and ferns. Palustrine forests, woodlands, and shrublands are often called swamps, forest seeps, or floodplain forests and thickets. Palustrine herbaceous openings are marshes, open seeps, and wet meadows; their terrestrial counterparts are meadows and grasslands.

The next differentiation in community types is based on the dominant species. Which species dominate a forest is generally the result of the site’s physical characteristics (soil, slope, aspect, soil moisture) and how environmental stresses (wind, ice, flood, drought) and past stewardship activities have affected the trees and the amount of shade they cast on the forest floor. Some species (often referred to as early successional or pioneer species) are shade-intolerant and require full sun conditions to colonize a site. Examples of shade-intolerant species in our region include sweet birch, eastern red-cedar, and quaking aspen. Species with intermediate shade tolerance include tuliptree, ashes, oaks, hickories, and red maple. These species can colonize both open areas and forest gaps that are not open enough for pioneer species. Shade-tolerant species such as sugar maple, eastern hemlock, and American beech have the ability to survive in low light conditions and can persist in the understory until canopy trees die. Because seedlings of shade-tolerant species can grow under low light conditions, these species are often able to maintain dominance until the site suffers a significant disturbance (high winds, extensive logging) that increases the amount of light reaching the forest floor, favoring intermediate or shade-intolerant species.

In Pennsylvania, most of the natural forest communities are dominated by deciduous broadleaf (hardwood) species. Communities dominated by conifers are limited to eastern hemlock-dominated stream valleys and wetlands and smaller edaphic communities such as barrens where Virginia pine and pitch pine often dominate. White pine often mixes into many forest community types and can be locally dominant. Abandoned plantations often including red pine, Norway spruce, white pine, and red spruce established in the middle part of the 20th century abound throughout the state. These are sometimes sizable but often relatively compact and scattered.

Currently, communities dominated by oak species are common in various parts of Pennsylvania, largely the result of three factors. One is the practice for thousands of years by Native Americans of managing the landscape using fire, which favors oak regeneration. Second is the decline of the American chestnut between 1910 and 1950 due to chestnut blight, an introduced fungus. Third is extensive clearcutting between 1850 and 1920 to supply the growing cities and towns with construction materials and fuel (firewood, charcoal). The high light conditions created by clearcutting and the subsequent wildfires preferentially favored oaks, which can tolerate fire better than most other native trees. Because there is now a general aversion to clearcutting and fire—although both are considered appropriate management practices when properly used—the conditions required to perpetuate oak dominance occur less often. With overabundant deer consuming much of the annual acorn crop and the few oak seedlings that do sprout, indications are that oak communities on many natural lands will eventually give way to red maple- and beech-dominated communities after the current canopy trees decline. However, any prediction of the future of forests in Pennsylvania will be challenged by new and established pests and diseases (the Asian long-horned beetle, beech leaf disease, hemlock wholly adelgid, etc.), climate change (warming temperatures will encourage southern species to spread into the region and northern species to decline), and our success with controlling the many well-established invasive species already here (e.g., spongy moth).

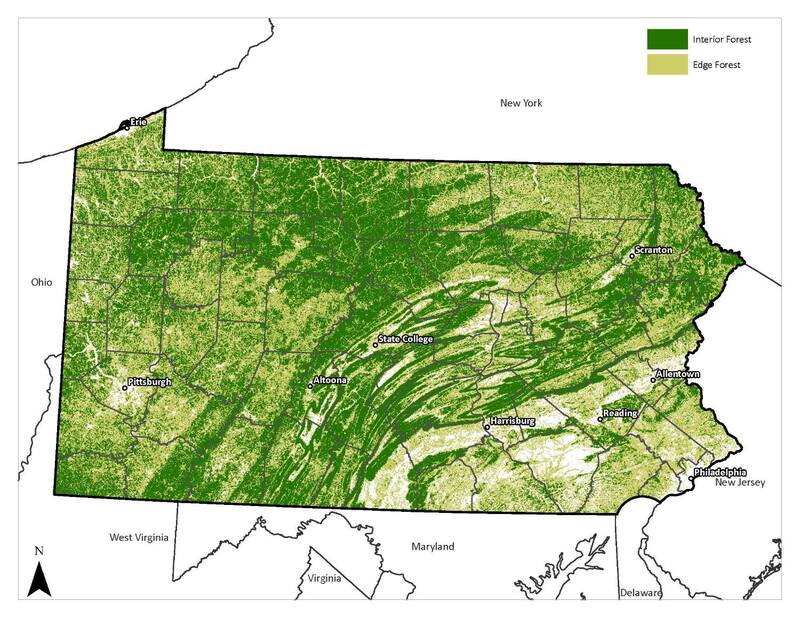

Because the state has been so fragmented and dominated by human use of the landscape, some wildlife species have been lost. In many areas, those wildlife species that remain are the ones more tolerant of human-dominated landscapes. “Backyard wildlife” species—raccoon, opossum, cottontail, voles, mice, American robin, European starling, gray catbird, mourning dove, blue jay, and white-tailed deer—abound under urban and suburban landscape conditions. Less tolerant wildlife, however, still occur in the more rural areas where large blocks of unbroken forest or grasslands create interior habitat, that is, areas sufficiently removed (100 meters or about 300 feet) from all edges between contrasting habitat types or developed land.

In interior habitat, wildlife encounter lower levels of predation and competition from the often abundant “backyard wildlife,” which prefer edges. Species in the sensitive category include black bear, bobcat, mink, river otter, and birds of interior forest (e.g., scarlet tanager, ovenbird, various other warblers) and grasslands (e.g., eastern meadowlark, bobolink, vesper sparrow). Typically, these more sensitive species occur in areas of larger, unbroken forest and grassland tracts of at least hundreds of acres. There are exceptions such as the federally protected bog turtle (Clemmys muhlenbergii), which inhabits relatively small wetlands throughout southeastern Pennsylvania.

In Pennsylvania, wildlife can only be managed directly through activities approved by the Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC) and Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC). These two agencies regulate hunting, trapping, and fishing within the state and support the protection of declining nongame species. Currently, some groups of wildlife species fall through the cracks in the jurisdictional net that the agencies cast in helping to protect them. One prominent group is terrestrial invertebrates. The species included in this group span many ecological niches across many natural communities and habitats and include most of our pollinators and primary food for birds, small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. If not federally listed, terrestrial invertebrates have no direct protection, although some are noted and considered during project reviews through the Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Index (PNDI) process, which assesses specified land areas for endangered, threatened, near threatened, and rare species. Many terrestrial invertebrates are now considered Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) within the State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP), and conservation activities can receive funding through State Wildlife Grants as administered by PGC and PFBC with funds received through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Natural areas managers can have a strong influence on the animal species that use a site through stewardship of the plant and water resources on which wildlife depend. Over the last few decades wildlife management has transitioned from a goal of maximizing edge-loving game species (deer, rabbit, pheasant) to an approach that emphasizes creating large blocks of contiguous forest and grassland to protect populations that depend on forest-interior and grassland-interior habitat.

Pennsylvania Plant Community Classification (naturalheritage.state.pa.us/Communities.aspx, as of 2024)